Rethinking Pathological Demand Avoidance

A mother recently visited my office seeking answers for her 12-year-old son.

“Every day feels like a battle. He resists everything I ask, no matter how small. From the moment I wake him up until bedtime, life at home feels unbearable. His siblings cooperate, but he argues constantly. I read about Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA), and I’m convinced he has it. Can you evaluate him?”

What Is PDA?

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) was first described in the 1980s by British psychologist Elizabeth Newson. She observed a group of autistic children who showed persistent and extreme resistance to everyday demands—behavior that did not align with the usual presentation of autism.

Growing Awareness of PDA

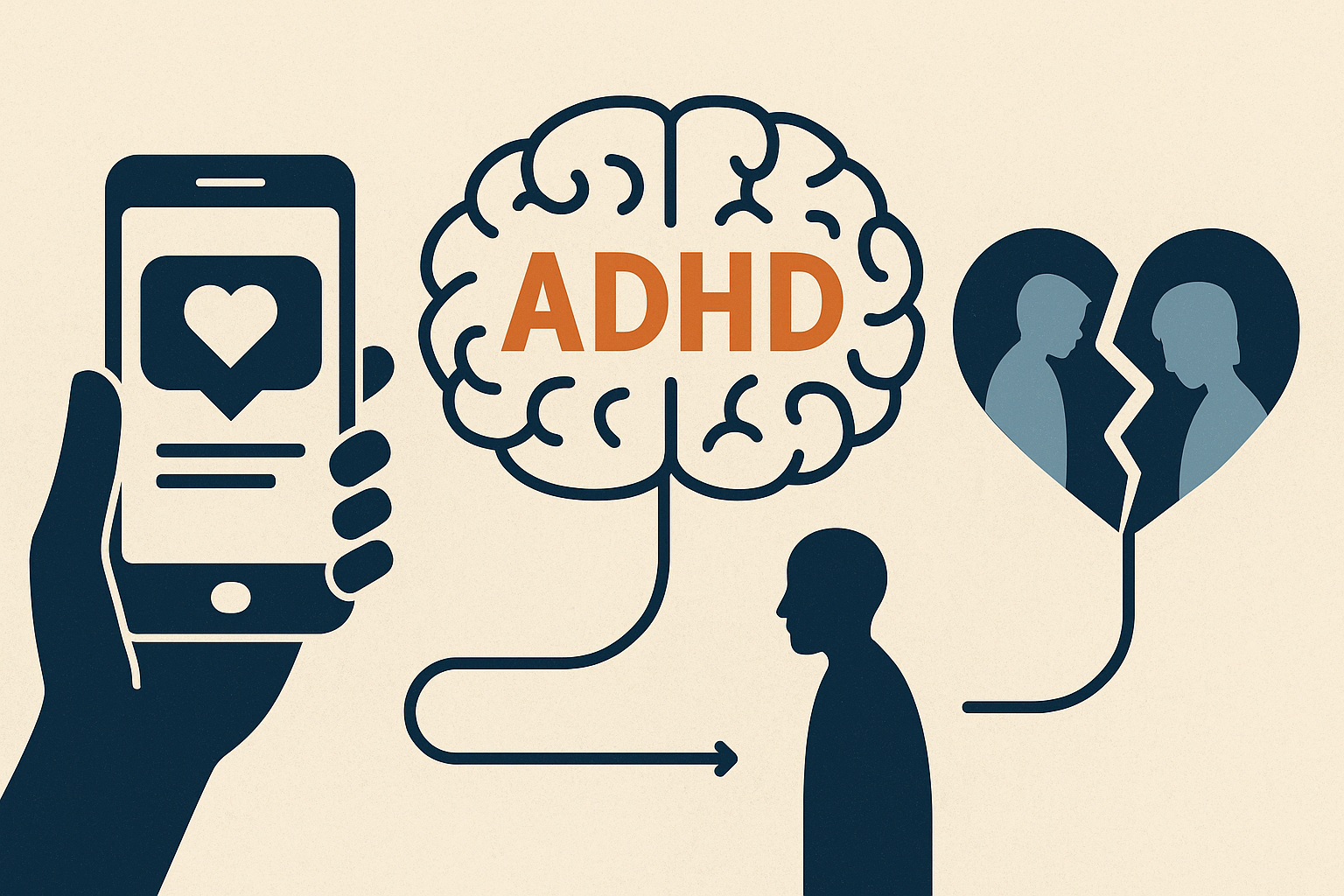

Although PDA has never been formally recognized as a psychiatric diagnosis, the concept gained traction in parenting circles through social media around 2010. Parents raising children who resist demands found comfort in the idea that PDA might explain their struggles. Online communities, especially on Facebook and TikTok, amplified these discussions and even gave rise to “low-demand parenting” approaches promoted by unlicensed coaches.

Why PDA Is Controversial

Research on PDA remains limited and often biased. Many studies rely on parents already convinced their child has PDA, which influences results. Moreover, PDA has expanded beyond autism contexts and is now suggested for children with ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, or even depression—despite little scientific backing.

The debate also extends to the underlying cause. Some believe anxiety drives demand avoidance, while others argue it stems from cognitive rigidity or temperamental traits. My own clinical experience suggests that many resistant children show no anxiety at the moment of refusal, but instead shift quickly to anger when demands persist.

Anxiety: Cause or Consequence?

It is possible that anxiety in these children emerges as a consequence of ongoing conflict with parents and teachers rather than as the root cause of their avoidance. Living in constant tension understandably fuels anxiety in both children and caregivers.

Alternative Perspectives and Treatment

Historically, psychologists have described demand-avoidant behavior as oppositional or noncompliant, and there are established, evidence-based treatments for such behaviors. By contrast, the “low-demand” approach lacks scientific validation. While it may temporarily reduce conflict, it risks leaving children unprepared for adult responsibilities.

Effective interventions, as Grahame et al. (2020) emphasize, should focus on helping children gradually build tolerance for uncertainty and external control. Learning to manage demands is a vital life skill, and treatment must balance reducing conflict with maintaining realistic expectations.

Conclusion

Whether we call it PDA or simply oppositional behavior, the essential truth is that some children struggle intensely with authority and expectations. Labels matter less than practical solutions grounded in science and compassion. Parents, above all, want guidance on how to support their children and restore peace to their families.