Autism as Difference, Not Deficit

For years, autism has often been framed through a medical lens that emphasizes deficits in communication. Autistic ways of speaking, connecting, or avoiding small talk were treated as problems that needed correction. Traditional approaches assumed that misunderstandings were caused by autistic people, who were then trained to adapt to non-autistic norms.

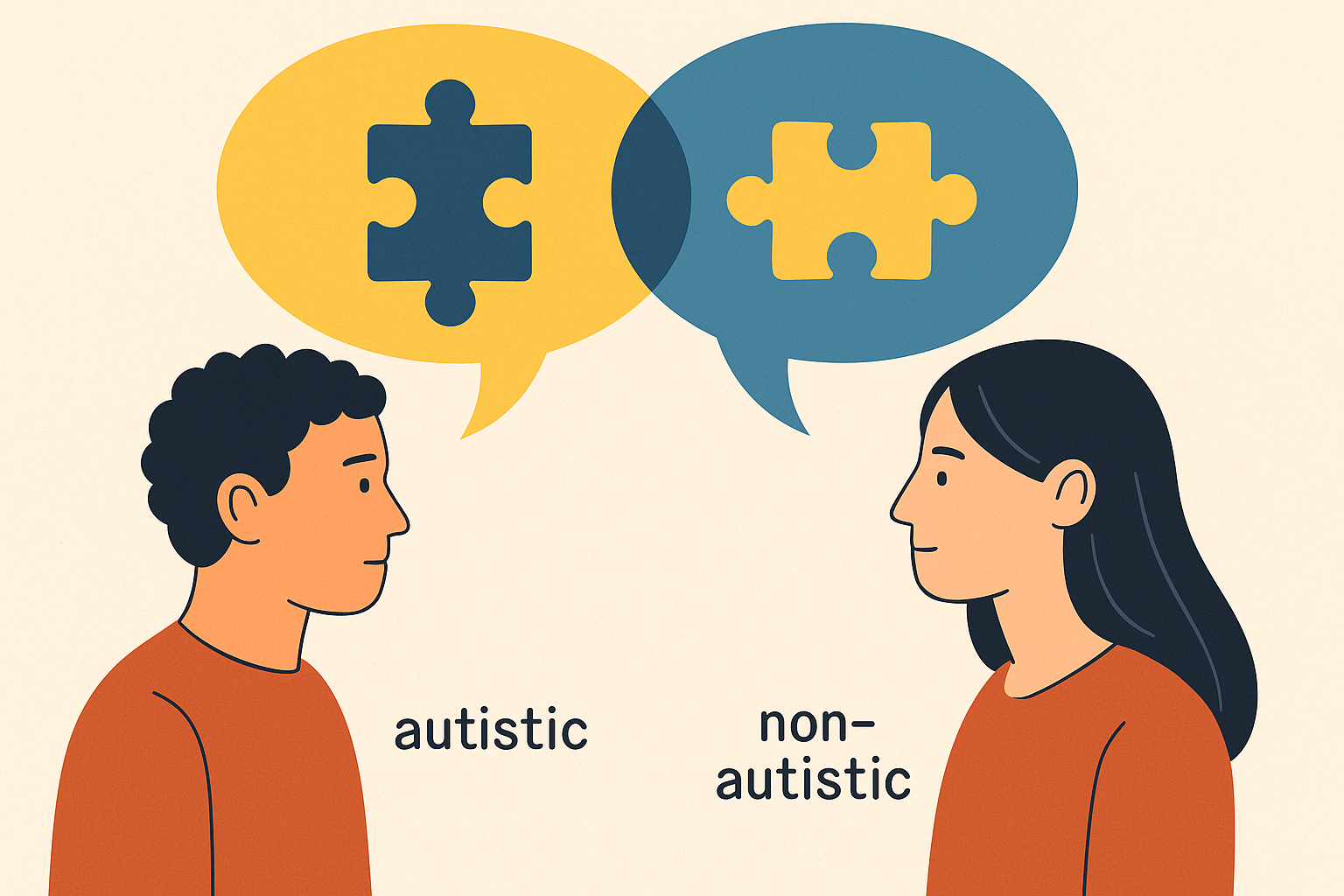

A newer perspective challenges this. Autism is not about lacking communication, but about having different styles of communication. The real difficulties often appear when autistic and non-autistic people interact. This idea is captured in Dr. Damian Milton’s “double empathy problem,” which explains that communication breaks down in both directions when people of different neurotypes struggle to understand each other.

For instance, small talk may feel pointless to many autistic people, while non-autistic individuals may see avoiding it as unfriendly. Both sides interpret the same moment differently, and both may feel misunderstood. Research confirms that autistic people generally communicate well with each other, just as non-autistic people do. The challenge emerges when communication styles collide.

Cross-Neurotype Encounters

Studies show that mixed groups of autistic and non-autistic individuals experience more frequent miscommunication compared to groups made up of only one neurotype. This suggests that autistic communication is not inherently flawed, but context-dependent—similar to cross-cultural differences.

A Cultural Comparison

Just as cultural norms vary across societies—such as greeting styles or expectations of politeness—neurotypes also carry their own rules of interaction. What feels respectful in one group may feel confusing in another. Recognizing these differences helps prevent unfair labeling of autistic communication as “wrong.”

Research Insights

Work by Dr. Catherine Crompton and colleagues supports this view. In experiments, autistic-only groups and non-autistic-only groups both maintained strong communication. Mixed groups, however, struggled more, with stories and details breaking down quickly. Other studies revealed that autistic pairs often reported genuine connection and were even rated by observers as having strong rapport.

Why It Matters

Shifting from a deficit-based model to a difference-based model has major implications:

- Social skills training should be reframed as learning tools for navigating different contexts, not as fixing a deficit.

- Autistic styles such as directness, focus on detail, or deep topic-sharing should be valued as authentic.

- Communication breakdowns should be seen as mismatches, not as one side being “wrong.”

Moving Toward Understanding

When people recognize that communication struggles arise from different styles rather than from flaws, empathy grows. Autistic people may still benefit from learning non-autistic norms for practical reasons, but these should be taught as situational tools rather than the “right” way to socialize. Equally, non-autistic people can learn about autistic ways of connecting to foster mutual understanding.

Seeing autism as difference, not deficit, allows both sides to build bridges, reduce shame, and create more inclusive human connections.