Complex Emotion Processing in Autistic Adults

Recognizing emotions accurately is fundamental for effective social interaction.

Psychologists often classify emotions into two main groups: basic emotions (such as anger, fear, disgust, happiness, sadness, and surprise) and complex emotions, which emerge from the combination of basic feelings, cognitive processes, and social or cultural influences.

Research has shown that Autistic adults may face challenges in recognizing basic emotions in certain situations. In laboratory experiments, for instance, they sometimes identify emotions from facial expressions less accurately than neurotypical adults.

Yet, recent findings suggest that their emotion recognition skills in real-world contexts may be stronger than previously assumed. Contextual elements—such as body language, gestures, and environmental cues—appear to enhance their ability to interpret emotions. In fact, Autistic adults may depend more on these additional cues than neurotypical individuals.

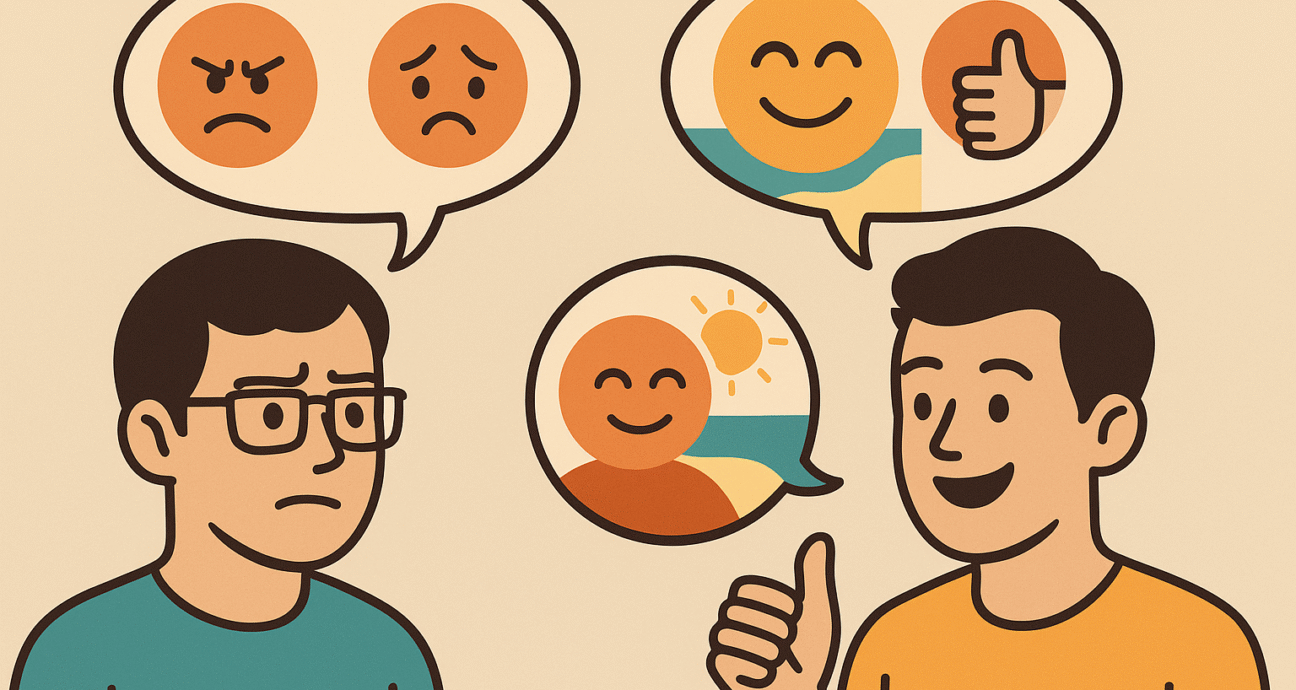

To investigate this, Kline and Blumberg (2025) conducted a study comparing young Autistic adults with peers who did not have neurological, developmental, or psychiatric conditions. Participants were asked to identify emotions in three different ways:

- Viewing only facial expressions.

- Viewing facial expressions combined with full-body expressions.

- Viewing facial and body expressions within a meaningful context (e.g., a smiling face and a thumbs-up on a sunny beach).

The results revealed that Autistic adults were most accurate when contextual and environmental cues were available, whereas neurotypical participants performed consistently well across all conditions.

The study suggests that Autistic adults process emotions differently, relying more heavily on contextual information. Importantly, when given sufficient cues, they identified emotions as accurately as neurotypical adults.

The researchers emphasized that past studies have often focused too narrowly on deficits rather than recognizing differences in emotion processing. Standard facial recognition tests may underestimate the emotional abilities of Autistic adults.

Understanding these strengths and unique strategies could reshape how we view emotional intelligence across diverse populations. Slower, context-based processing may even offer benefits in certain situations.Future social communication interventions might therefore incorporate contextual and non-facial cues, enabling Autistic adults to leverage their strengths in real-world emotional understanding.