Medical Trauma and the Hidden Roots of Eating Disorders

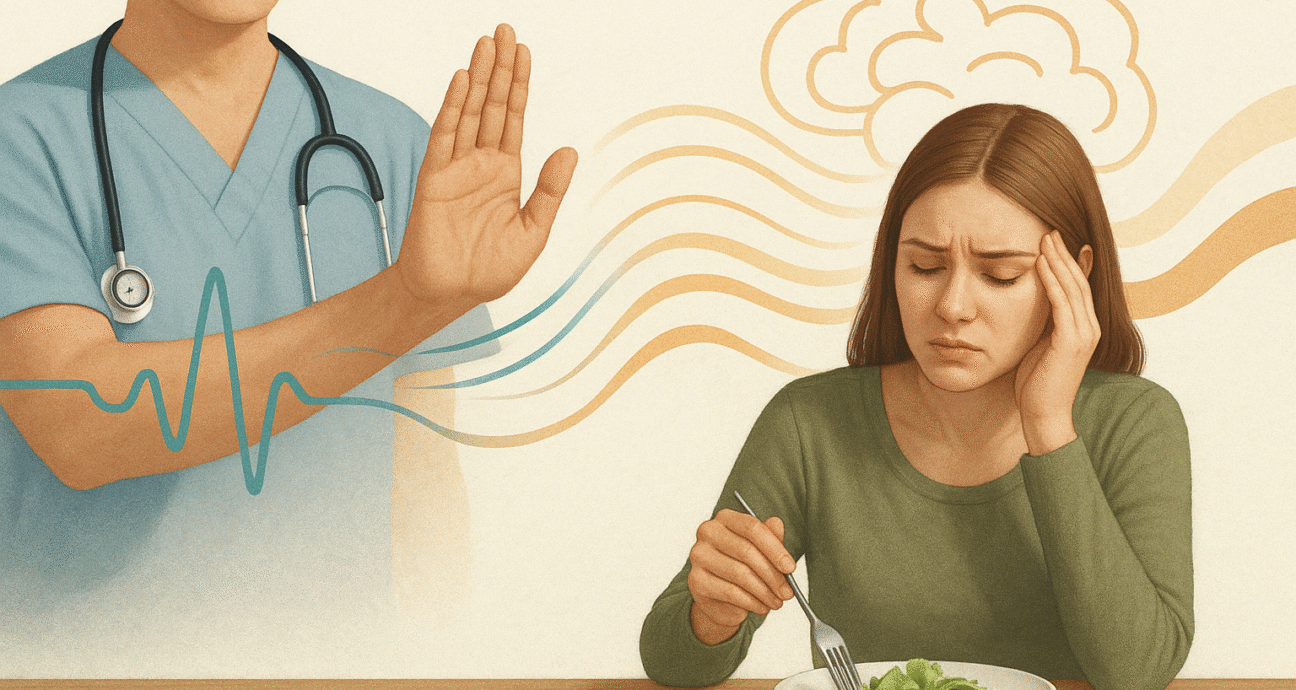

Chronic conditions like migraines, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) are often discussed as purely physical illnesses. Yet for many, they signal something deeper, a rupture in trust between patient and healthcare provider. Years of being dismissed, misdiagnosed, or told “it’s just stress” can leave emotional scars that reach far beyond the body, shaping how people relate to their health, and in many cases, to food.

Medical Trauma

Medical trauma occurs when medical experiences create lasting feelings of fear, shame, or powerlessness. It can arise not only from invasive procedures, but from repeated invalidation by professionals who minimize symptoms. This pattern disproportionately affects women and people of color, whose pain is frequently questioned. Over time, this erodes confidence in one’s own body and in the very system meant to heal it.

For many struggling with eating disorders, the connection is striking. When medicine fails to bring relief and the body feels unsafe, food becomes one controllable element. Restricting diets, fasting, or “clean eating” can feel like ways to regain order when everything else feels uncertain. At first, these behaviors may even be encouraged by medical advice—but over time, they can evolve into rigid rituals reflecting the vigilance of trauma itself.

Research supports this overlap: people with medical trauma often show heightened anxiety, body distrust, and perfectionism—all of which are strong predictors of restrictive eating. Some develop hypersensitivity to internal cues—each stomach cramp feels alarming—while others disconnect from bodily sensations altogether, a learned detachment from chronic pain or disbelief. Both make it difficult to interpret hunger or fullness, setting the stage for disordered eating that feels protective, even logical, after medical harm.

Biologically, trauma activates the body’s stress response, elevating cortisol and disrupting digestion, appetite, and hormones. These same disruptions can worsen pain, menstrual issues, or gut distress, reinforcing the cycle of medical anxiety and control.

Recovery

Healing begins when the pattern is named. Seeing medical trauma as part of the narrative reframes the eating disorder not as defiance, but as an attempt to feel safe in a distrusted body. True recovery involves rebuilding trust, with one’s own sensations and with the medical system itself.

Clinicians can help by asking about past experiences, validating fears, and practicing trauma-informed care based on empathy, predictability and choice. When patients feel seen and heard, medical environments can shift from retraumatizing to reparative, allowing individuals to rediscover their bodies as allies, not threats.